Home / Sunday-mid-day / / Article /

Why Mirza Wajid Ali Shah’s legacy goes beyond kathak

Updated On: 02 July, 2023 08:32 AM IST | Mumbai | Aastha Atray Banan

A London-based professor researching the evolution of Hindustani music during the colonial rule, credits the last king of Awadh for his experimental and innovative pursuit of music

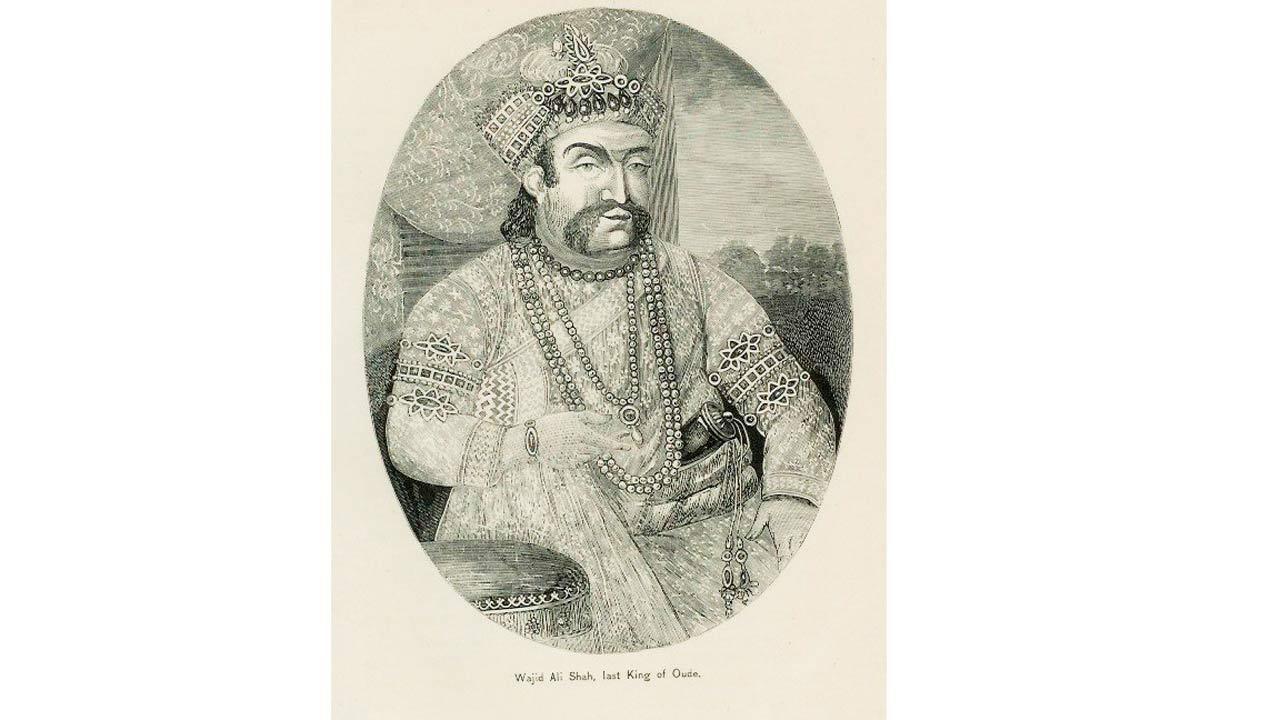

Mirza Wajid Ali Shah was a singer, dancer, and played the sitar and drums. His courts, says Williams, were always full of musical innovations. Pic/Wikimedia Commons

Richard Williams, senior lecturer in music and South Asian studies at the SOAS University of London, first got interested in Indian classical music when he visited Vrindavan a few years ago. “I met these priests and was collecting poetry from the 18th century, and then, they asked me to drop by in the evening. There was a ceremony where they sang these poems, and I realised that if I factored out music, I would be missing out on a lot,” recalls Williams.

The musical evening led him on a completely different journey. Later, while pursuing his PhD at King’s College, Dr Katherine Butler Schofield, a historian of music and listening in Mughal India and the paracolonial Indian Ocean, told him about the last king of Awadh, Mirza Wajid Ali Shah, and the time he moved to Calcutta. “She suggested I find out more about him, and then I did, and he was quite a character,” he says over a video call from London. His research has now taken shape as a book, The Scattered Court: Hindustani Music in Colonial Bengal (Chicago University Press), where Williams focuses on the creation of music post 1857, and the courts of Wajid Ali Shah.