The Ramayanas you haven’t read

Updated On: 12 November, 2023 07:28 AM IST | Mumbai | Sumedha Raikar Mhatre

A new book delves into the quaint and lesser-known narratives that run parallel to the popular Ramayana, like the one sung by Kerala’s Malabari Muslims, demonstrating the epic’s acceptance across cultures

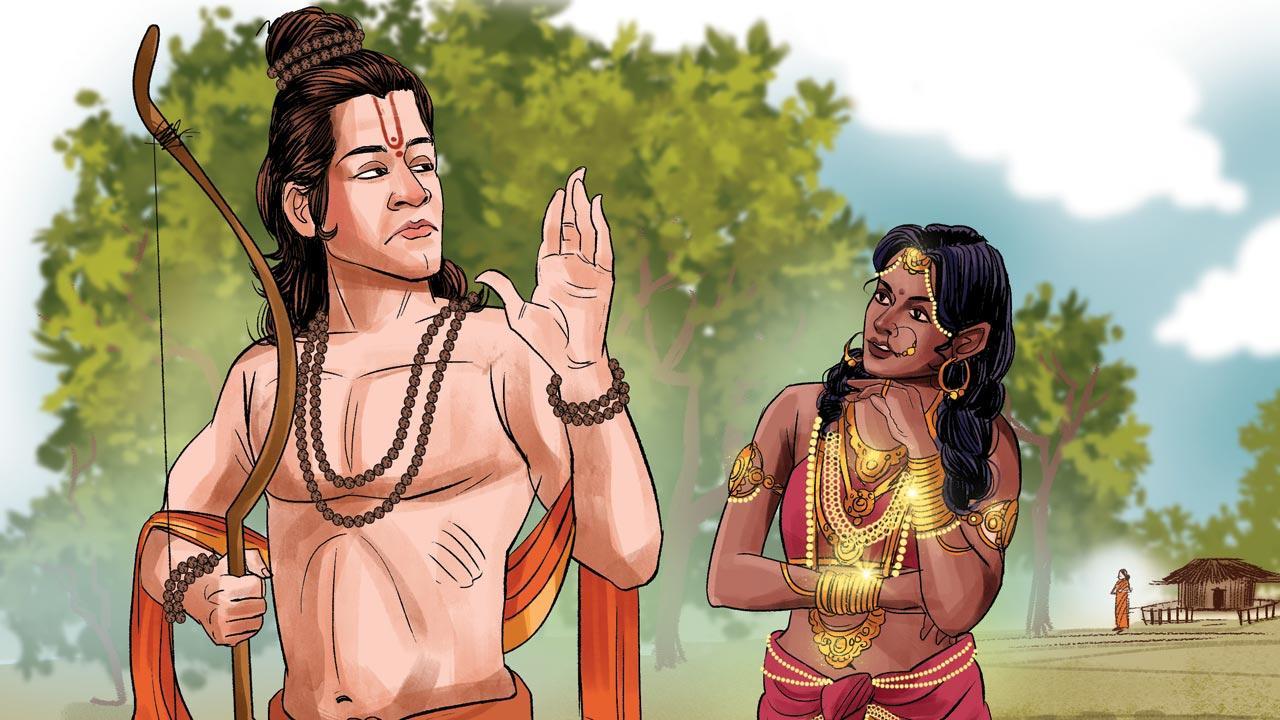

The book shows the progression of epics across cultures—whether it is the non-Sanskrit Mewati folk Mahabharata, or the Bhili Bharath adivasi oral text of the Dungri Bhils. Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() Beevi Surpanakha “dyes her scattered grey hair with charcoal and honey” and “greedily decks up with her late grand aunt’s gold”. She tracks Lama and then proposes to him. Lama invokes Shariat to evade her sexual advances. But Surpanakha asks why a woman is not allowed to keep multiple men, if the Islamic law allows men to engage with four or five women.

Beevi Surpanakha “dyes her scattered grey hair with charcoal and honey” and “greedily decks up with her late grand aunt’s gold”. She tracks Lama and then proposes to him. Lama invokes Shariat to evade her sexual advances. But Surpanakha asks why a woman is not allowed to keep multiple men, if the Islamic law allows men to engage with four or five women.

The conversation between Lama and Surpanakha is laced with quick-wit and sarcasm in the indigenous Malabar Mappila language of northern Kerala spoken by Muslims. The repartee is one of the highlights of the Mappila Ramayanam, an adaptation-retelling of Valmiki Ramayana, which shares striking similarities with Mappillappattu—the 700 year-old song tradition of the Muslims of Malabar. The base language of these songs is a unique fusion of Arabic and Malayalam. Even today, children in Muslim homes are treated to Mappila isals (soothing fast notes) during bedtime. And the women, not quite empowered to speak on love and sexuality in public, find solace in quoting a Hindu epic character’s attack on patriarchy. They are happy to take recourse in a character who fights dogma.